By Jack Jager and Michael Drew

The RealityChart™ (cause-and-effect chart) that you generate during a Root Cause Analysis investigation is important as it creates a common understanding of why the problem has occurred.

The RealityChart™ (cause-and-effect chart) that you generate during a Root Cause Analysis investigation is important as it creates a common understanding of why the problem has occurred.

Creating your RealityChart™ starts with finding the causes that contributed, or played a part, in the event or problem that occurred. During this phase of the analysis, the chart serves as the interactive platform where all of the information is captured, recorded, and organized. The chart should be highly visible so that all group members can see and comment on it.

(Tip: If you build your initial chart using “Post-It®” notes, attaching them to a vertical surface is best. Use dark coloured, thick marker pen for writing. This simply makes the information more readable. If you want to move your chart, post the notes on a roll of brown paper which can be rolled up and moved. Using RealityCharting™ allows the chart to be shared electronically)

The second challenge in the creation of the RealityChart™ is to arrange the causes in a meaningful, logical way that other people can follow and understand. The crucial point here is whether other people can understand the chart, not just you. This is the real litmus test for the chart and can be a challenge. Whilst you may believe that your chart is sound, if other people can’t follow it then it might possibly be subjected to scrutiny, be dissected at every turn, and perhaps even be dismissed if believed to be an inaccurate representation of the problem. Be prepared as others view your chart to listen to what they think, you may discover alternative paths or additional causes that you or the team could not see.

So, to ensure your chart is a good representation of the problem analysis, challenge your charts and be open to other views.

How do you do that?

I’m going to tell you about two ways – Testing your logic and applying “rules check”.

1) Test your logic

Remember there are three important things about charts – Logic, Logic, and Logic! If the logic is sound then the connection should be logical in both directions. What I mean is, if A is caused by B and C, then the converse of this must also be true - B and C cause A.

If you use this test and the statement doesn’t ring true then the connection needs to be changed so that it becomes logical.

Here’s an example.

How often have you heard that you have a “failed bearing” and that this is caused by a “lack of lubrication”? Now whilst this may be true, and it does have the semblance of a logical connection, there is much that happens in between these two causes.

How does it sound when you state the connection the opposite way: Whenever you have a lack of lubrication, you will have a failed bearing. Now this just doesn’t sound right. It is not always true. This understanding indicates that there are other causes that have yet to be found.

What happened to the causes of “metal to metal contact”, “generation of heat”, “expansion of metal”, “narrow tolerances”, “bearing in use”, “lack of monitoring”, “no tripping mechanism”, “extreme heat”, severe duty and so on? There is a lot more information here than meets the eye.

A lack of lubrication itself does not cause the bearing to fail - not instantaneously. A lot of things happen before you have catastrophic failure of the bearing. So the initial statement that you have a “failed bearing” being caused by a “lack of lubrication” is far too simplistic. It is a generalisation that requires a lot of assumptions to be made.

Your job is to present the facts in a logical arrangement rather than allowing or forcing people to make guesses based on insufficient information. The adding of more specific details (even what some people consider to be superfluous detail) can be very beneficial in facilitating this. It is the detail that allows comprehensive understanding of your chart.

2) Apply the “Rules Check”

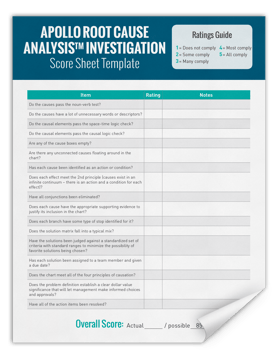

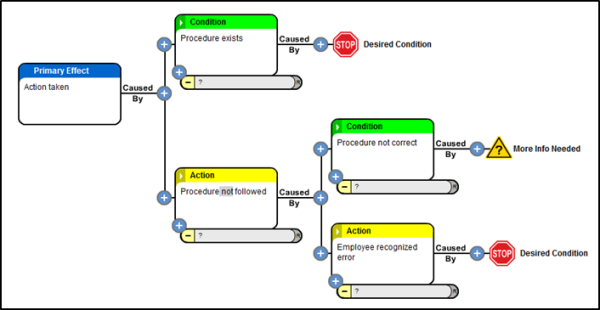

When using the Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology, your RealityChart™ must have:

Evidence to support each of the causes.

This validates the information which gives the chart credibility.

Stop points indicated and a reason for stopping also provided.

This indicates to everyone that you have stopped asking questions on that causal path and have provided a valid reason for doing so. When all cause paths have been completed in this manner, then the chart is finished.

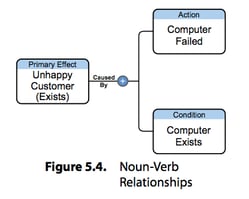

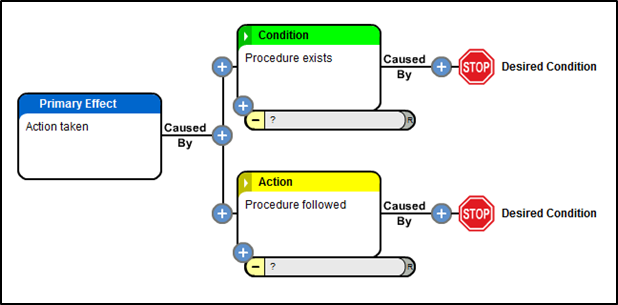

Causes should be labelled as either actions or conditions.

This helps you to see what type of causes you have found and therefore what may have been missed. It drives the questioning process to another level.

Each connection should have a least one action and also one condition.

Though typically we see more conditions than actions, we should never see a straight line of causes within a chart. This too should generate the asking of more questions.

Any anomalies or violations to these “rules” should demand that another question be asked. The anomaly, or violation, must be challenged.

It is the challenge that is important. Challenging the cause and effect charts consistently will improve the quality of the charts. It is about dotting the “I”s and crossing the “T”s. That said, there is no such thing as a correct chart – they are always a work in progress. They are rarely if ever “perfect”.

The initial chart should be considered a draft and is a direct reflection of the information you have available and the amount of time that you have to organize and challenge it. As the chart continues to develop, challenge it constantly using the logic test and the rules check.

Significantly, a quality chart will enable you to demonstrate the effect that your corrective actions will have on the problem or event. If you eliminate or control a cause that forms part of a causal relationship, then whatever happens after that point is effectively prevented from occurring and you can demonstrate this very effectively by referring to a detailed, logical chart.

Added benefits:

-

Once a quality chart has been produced for a systemic, recurring failure, that chart could be used as a template and rolled out when similar failures occur. Then, it’s a matter of challenging the chart to see if the information is all correct.

How much time would this save your organization in investigations? How much time would it save your organization to solve systemic issues that are eliminated?

-

A “quality” chart can be a learning tool. It can be shared amongst colleagues as a resource that shows what to look for when similar problems arise.

Summary

A RealityChart™ is a dynamic view of the logical cause and effect relationships that represents the logic as to why a problem has occurred. They can be shared, challenged and changed over time. They lead to effective solutions for one off and systemic problems.

Demand excellence in your charts. The effort in trying to achieve this will be time well spent.

One colleague stated that another must understand this concept since he has an engineering background, and all engineers would know this. I had to inform them that I also have a 30-year background in engineering,

One colleague stated that another must understand this concept since he has an engineering background, and all engineers would know this. I had to inform them that I also have a 30-year background in engineering,

Author: Kevin Stewart

Author: Kevin Stewart

The

The

.png?width=603&height=283&name=figure_1_(templates_blog).png)

-resized-600.png)