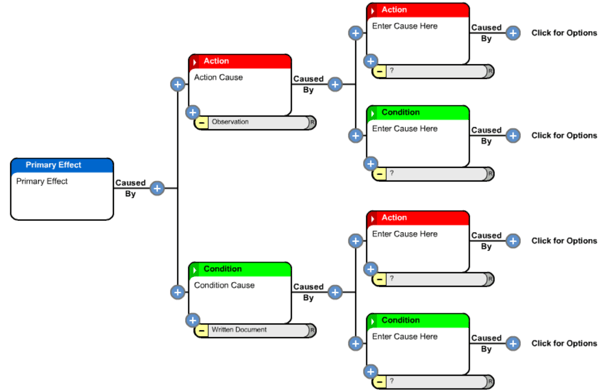

One of the four basic principles in the Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology is that for each effect there are at least two causes and these causes are either actions or conditions.

This principle causes you to think more critically, challenge causal relationships more consistently, and to understand that things are rarely as simple as they may seem.

One implication of this principle is that there should never be a straight line, or even a partial straight line of causes within a cause and effect chart. A straight line tells us that there are other causes that still need to be found or identified, and more questions must be asked.

In each causal connection we should see at least one action cause and one condition cause.

So what are actions and conditions?

Conditions exist—they refer to the current state of things. Take gravity for instance—it is there all the time. Gravity exists. So this cause would be a conditional cause.

Conditions must exist. They always exist alongside of any action.

An action cause is a cause which makes use of the available conditions. If the conditions didn’t exist, then the action would have no effect at all. The action cause is that moment in time when something happens. It is the thing that is different—the instigator or the catalyst of the effect that occurs.

Typically, there is one action and several conditions. Many of the action causes are also related to the things that people do. Action causes are readily seen and tend to be easily identified. When people tell the story of what happened they often list a series of actions, and relatively few conditions. When we create a timeline or sequence of events, the initial straight line will be constructed mostly of actions.

The Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology demands an exhaustive search for both condition causes and action causes. If you only see half of the problem, will you really understand it? If you only find half of the causes, you will also only have half of the opportunities for controlling or mitigating the problem to an acceptable level.

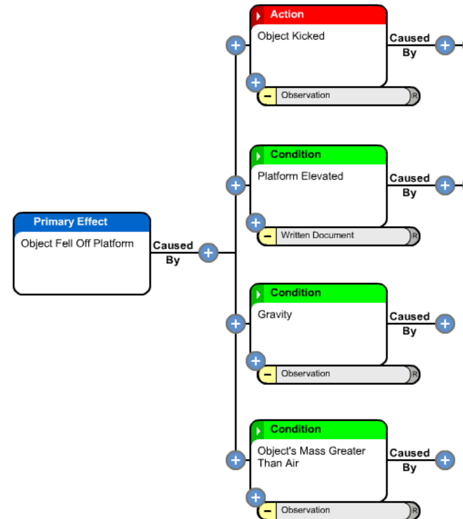

Let’s take a look at an example – “An Object Fell Off a Platform”

“What happened to make the object fall?” would be a good question to ask. Let’s say someone kicked it off the platform. This is the direct cause of why the object fell, so this is considered an action cause. It is the ‘something’ that happened. An action cause will typically be described using a noun/verb connection as in ‘object /kicked.’

But it’s not always that simple. There are other causes that have played a role in this scenario. At this point in time it is important to challenge the concept of the linear connection of causes and keep searching for more.

The “Every Time Statement”

A useful tool to apply in this scenario is an “Every Time Statement.” The statement itself should be absolute in the sense that all causes in the connection need to be present. The same effect should happen each time the action occurs.

So, every time you kick the object off the platform it will fall? No, not every time.

Why not? Because, the object in question must be elevated. If you kick it while it is on the ground it will not fall.

So is this an action cause or a condition cause?

It is a state of where the object was at the time it was kicked. So in this instance this cause would be labelled as a condition.

Now that another cause has been identified, you can repeat the “Every Time Statement.”

Every time you kick the object off the platform and the platform is elevated, the object will fall. Every time? Well, it will only be true if there is gravity in play. If there is no gravity present, then this statement will not be true.

Is gravity an action or a condition? It’s not an event, it just exists. It was there when the problem occurred. This means that we would label this cause as a condition.

There are now three causes in this causal relationship, but have we identified every cause in that causal connection? At this point we have:

- Kicked object off platform

- The platform was elevated

- Gravity was present

Will the object fall every time? Only if the object has a mass which is greater than that of air. If it were lighter than air, then it would not fall.

Is this cause an action or a condition? Again we observe that the object’s mass didn’t change. Its mass was what it was before the incident and had been so for some time. This makes this cause a condition.

Encourage people in the RCA group to actively look for the exception that makes a lie out of the “Every Time Statement.” Every time you find an exception to this statement you have effectively identified another cause. Add it to your list of causes and repeat the “Every Time Statement.” When you can’t identify any other exceptions then you should have effectively identified every cause in that causal connection. The statement should now be absolute.

So what we have identified here is that there are at least four causes in this causal relationship that will influence whether an object will fall or not. In fact, every time something falls the same types of causes will be in play. The action cause will still need to occur, but this may come in different forms. The action can be different but it will still make use of the available conditions.

To Sum Things Up

It is valuable to be able to label causes as either actions or conditions. The process of labelling causes demands that you find multiple causes for each connection. This in itself will challenge your understanding of the problem.

Understanding what the conditional causes are will also lead you to finding the most effective solutions for your problem - the hard controls. By actively engaging in challenging the logic of each and every connection within the cause and effect chart consistently, many more conditional causes will be found and more options of control will present themselves. When you have the ability to eliminate a conditional cause, substitute it, or engineer it out, then your solutions and their outcomes will be more consistent, reliable, and predictable. You can therefore, with a fair degree of certainty, declare that the problem will not recur.

1) A structure to support training

1) A structure to support training