By Kevin Stewart

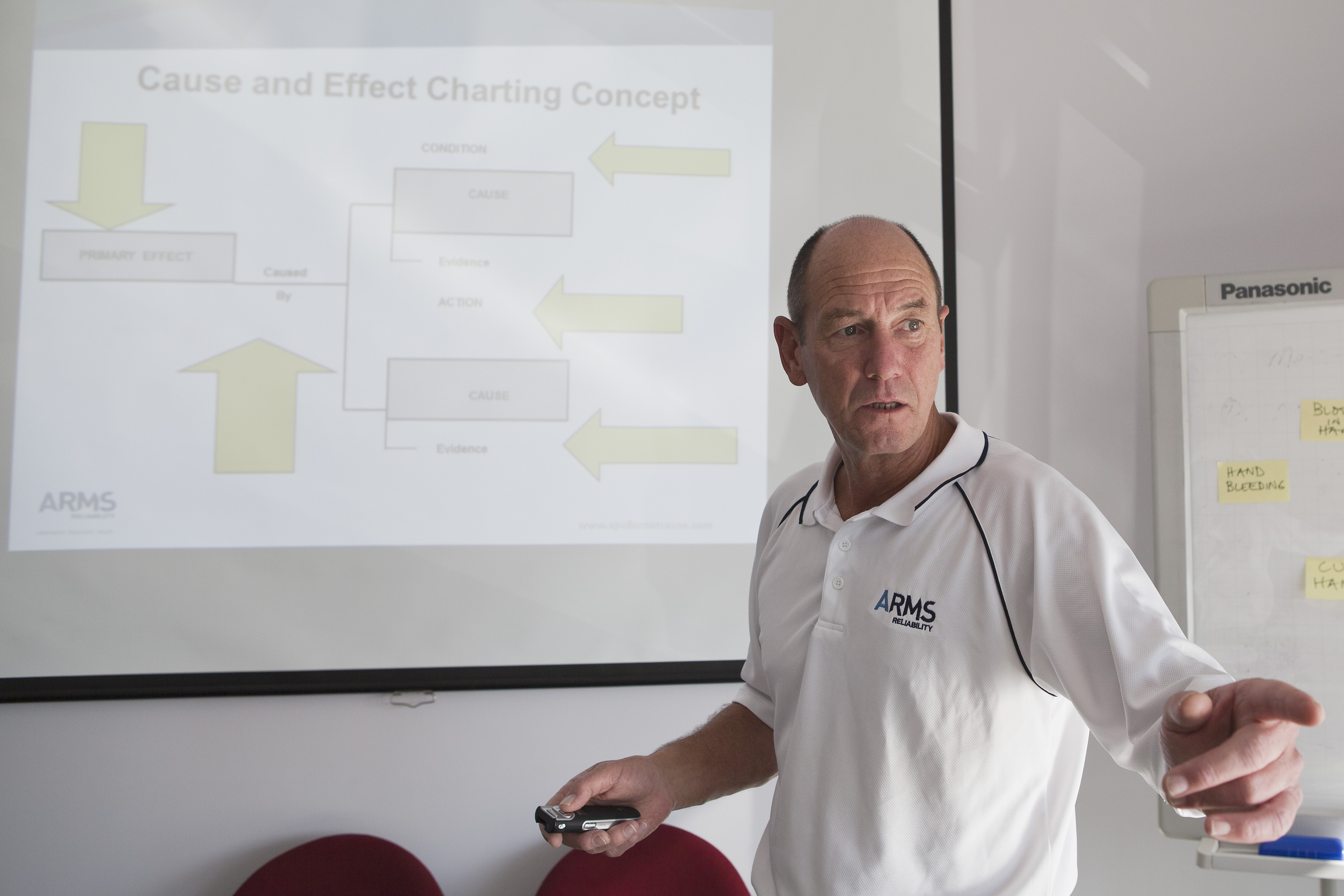

A facilitator conducting a Root Cause Analysis using the Apollo method performs a crucial role throughout an investigation. Here are some tips and steps to keep in mind when facilitating:

Over many years, I repeatedly hear that the ‘Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology is only used for big, serious investigations.’ This statement always makes me smile – because it is completely untrue.

An RCA using the Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology can be performed on any problem, large or small, as long as the right facilitator is on board. This article, part 1 of 2, explores the strategies and processes a facilitator should keep in mind when an investigation proceeds.

ANYONE CAN FACILITATE

In my Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology training classes, I always ask whether anyone is a certified facilitator. I’ve only received one ‘yes’ from the 2,000 or so students that have attended my courses. This sole person will have been trained in how to manage a group of different personalities; how to progress a group towards its goal; how to be firm and fair; and so on.

Yes, these are valuable skills to learn. And, in an ideal world, every facilitator would have the time and resources to complete the training. But you can facilitate a Root Cause Analysis using the Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology without this certification.

Facilitating RCAs requires flexibility – yet it also requires that you follow a standard outline. While every RCA has its own path, it will generally adhere to these main steps:

- Gather information

- Define the problem

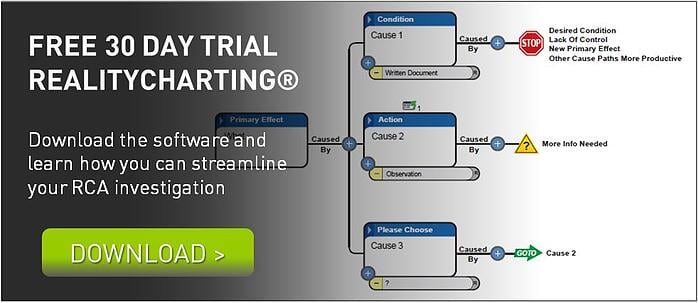

- Create a Realitychart

a. Phase one: Create the draft RealityChart™

b. Phase two: finish and formalise the RealityChart™ - Identify solutions

- Finalise the report

The process – as laid out above in its basic format – may look a little daunting to someone who has never facilitated an RCA before. Particularly, if you are contending with other feelings – like being anxious in front of a crowd, or feeling responsible for the outcome. You will need to deal with these latter issues in your own way.

What you can take charge of is finding a way to shape a group of disparate people into a highly functioning team, who share the common goal of reaching a solution. By following the steps below, you can prepare for a smooth facilitation process.

PREPARING FOR A FACILITATION

Step 1. Familiarise yourself with the Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology.

First, ensure you are familiar with the Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology – after all, it’s what you’re trying to facilitate. If you need a review, the RealityCharting™ learning centre is a great place to visit to recap on the basics. Here, you can complete a simulated scenario to really fine-tune your understanding of the process. It would also be a good idea to review the facilitation guidelines in the manual that you received with your original training. It gives an excellent overview of the entire process.

Step 2. Gather your supplies.

Stock up on post-it notes – and get the good, super-sticky ones that will stay on the wall.

We suggest that you use post-it notes instead of a computer to perform the analysis, as these help to enhance the common reality. With post-it notes, all participants can see what’s happening.

If you think the analysis will take a few days, get multiple colours of post-it notes so you can easily distinguish between the changes to the chart created on different days or at different times.

Ensure the room you’re working in has plenty of wall space. And, if the walls are unsuitable for post-it notes, tape poster paper to the wall first and then adhere your post-its. Using paper can provide the extra advantage of making the chart easy to remove and take with you. If it’s sensitive subject matter, you can roll it up and take it with you at the end of the day.

Step 3. Prepare the participants.

Ensure that all participants know what to expect before beginning an RCA. An RCA can require a significant time commitment, so make it clear from the outset how much time is needed from them.

Step 4. Gather information.

The more information you have at the outset, the smoother the journey.

You may already have information at hand in the form of pictures, emails, reports, write-ups, witness statements, and so on. There may be some useful physical evidence. Request evidence from the right people, collect it and store in the one file.

You may also choose to take the entire team to see the area under investigation, so that everyone has a clear picture in mind about what you’re discussing.

Be aware that, no matter how hard you try, there will always be some missing information. This is not a problem. You can call someone, look it up at the time, or make an action item for someone to gather the evidence later.

This basic premise is the reason that the RCA is done.

This basic premise is the reason that the RCA is done. et the answer is not a simple or straight forward one. Do we believe that the person(s) creating these corrective actions aren't trying to do their best? No, I don’t think so. I firmly believe that almost all people are trying to do their best. So where does that leave us?

et the answer is not a simple or straight forward one. Do we believe that the person(s) creating these corrective actions aren't trying to do their best? No, I don’t think so. I firmly believe that almost all people are trying to do their best. So where does that leave us?

he significance of the particular event can then be intensified because the variety and depth of the participants’ emotional responses are undeniably “real” and can, if not appropriately accommodated in the total incident management process, cloud the judgement of the investigator/s and even complicate the task for the team of analysts assembled for the RCA. Minimising the risk of friction, avoiding undue “heat” being generated by the harm (nearly) caused, can be achieved by the prompt application of an investigation process which both encourages and relies upon the frank sharing of information in order to achieve the agreed objective.

he significance of the particular event can then be intensified because the variety and depth of the participants’ emotional responses are undeniably “real” and can, if not appropriately accommodated in the total incident management process, cloud the judgement of the investigator/s and even complicate the task for the team of analysts assembled for the RCA. Minimising the risk of friction, avoiding undue “heat” being generated by the harm (nearly) caused, can be achieved by the prompt application of an investigation process which both encourages and relies upon the frank sharing of information in order to achieve the agreed objective.

stipulated a maximum of two hours for an RCA to be conducted in his organisation. Another expects at least “brainstormed” solutions before the conclusion of day one – within 6 or 7 hours. It is not uncommon for a draft report to be required within 48 hours of the RCA.

stipulated a maximum of two hours for an RCA to be conducted in his organisation. Another expects at least “brainstormed” solutions before the conclusion of day one – within 6 or 7 hours. It is not uncommon for a draft report to be required within 48 hours of the RCA.

nfortunately I can’t speak for other processes since the company I worked for standardized on the Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology early on. Since it worked for us we decided to spend our time using it instead of looking for the best process. (I would be interested in others’ comments about generating a common reality utilizing other processes.) So, my comments are from a single perspective but to use an old phrase – don’t tell me it can’t work – when others are doing it! Hopefully other processes have equal success in this important aspect of RCA work.

nfortunately I can’t speak for other processes since the company I worked for standardized on the Apollo Root Cause Analysis methodology early on. Since it worked for us we decided to spend our time using it instead of looking for the best process. (I would be interested in others’ comments about generating a common reality utilizing other processes.) So, my comments are from a single perspective but to use an old phrase – don’t tell me it can’t work – when others are doing it! Hopefully other processes have equal success in this important aspect of RCA work. 1) A structure to support training

1) A structure to support training