Author: David Wilbur, CEO - Vetergy Group

To begin we must draw the distinction between error and failure. Error describes something that is not correct or a mistake; operationally this would be a wrong decision or action. Failure is the lack of success; operationally this is a measureable output where objectives were not met. Failures audit our operational performance, unfortunately quite often with catastrophic consequences; irredeemable financial impact, loss of equipment, irreversible environmental impact or loss of life. Failure occurs when an unrecognized and uninterrupted error becomes an incident that disrupts operations.

Individual Centered Approach

The traditional approach to achieving reliable human performance centers on individuals and the elimination of error and waste. Human error is the basis of study with the belief that in order to prevent failures we must eliminate human error or the potential for it. Systems are designed to create predictability and reliability through skills training, equipment design, automation, supervision and process controls.

The fundamental assumptions are that people are erratic and unpredictable, that highly trained and experienced operators do not make mistakes and that tightly coupled complex systems with prescribed operations will keep performance within acceptable tolerances to eliminate error and create safety and viability.

This approach can only produce a limited return on investment. As a result, many organizations experience a plateau in performance and seek enhanced methods to improve and close gaps in performance.

An Alternative Philosophy

Error is embraced rather than evaded; sources of error are minimized and programs focus on recognition of error in order to disturb the pathway of error to becoming failure.

Slight exception notwithstanding, we must understand people do not set out to cause failure, rather their desire is to succeed. People are a component of an integrated, multi-dimensional operating framework. In fact, human beings are the spring of resiliency in operations. Operators have an irreplaceable capacity to recognize and correct for error and adapt to changes in operating conditions, design variances and unanticipated circumstances.

In this approach, human error is accepted as ubiquitous and cannot be categorically eliminated through engineering, automation or process controls. Error is embraced as a system product rather than an obstacle; sources of error are minimized and programs focus on recognition of error in order to disturb its pathway to becoming failure. System complexity does not assure safety. While system safety components mitigate risk, as systems become more complex, error becomes obscure and difficult to recognize and manage.

Concentrating on individuals creates a culture of protectionism and blame, which worsens the obscurity of error. A better philosophy distributes accountability for variance and promotes a culture of transparency, problem solving and improvement. Leading this shift can only begin at the organizational level through leadership and example.

The Operational Juncture™

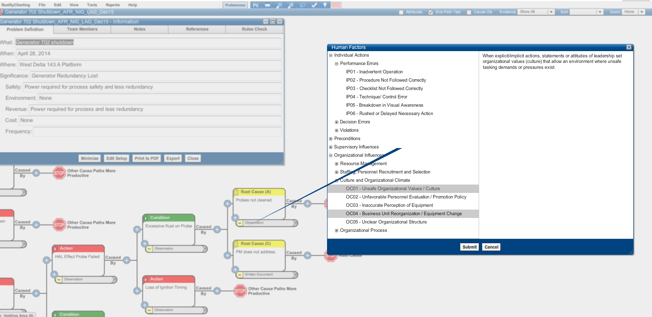

In contrast to the individual-centered view, a better approach to creating Operational Resilience is formed around the smallest unit of Human Factors Analysis called the Operational Juncture™. The Operational Juncture describes the concurrence of people given a task to operate tools and equipment guided by conflicting objectives within an operational setting including physical, technological, and regulatory pressures provided with information where choices are made that lead to outcomes, both desirable and undesirable.

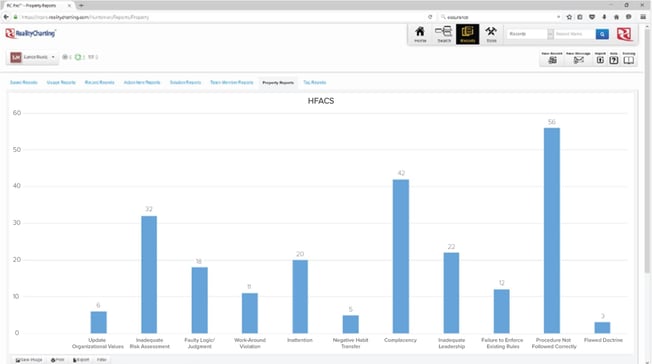

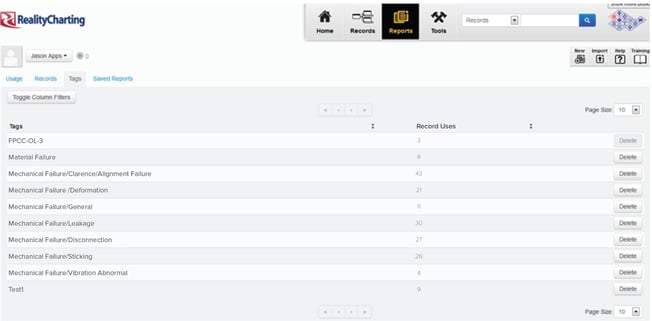

It is within this multidimensional concurrence we can influence the reliability of human performance. Understanding this concurrence directs us away from blaming individuals and towards determining why the system responded the way it did in order to modify the structure. Starting at this juncture, we can preemptively design operational systems and reactively probe causes of failure. We view a holistic assignment of accountability fixing away from merely the actions of individuals towards all of the components that make up the Operational Juncture. This is not a wholesale change in the way safety systems function, but an enhanced viewpoint that captures deeper, more meaningful and more effective ways to generate profitable and safe operations.

A practical approach to analyzing human factors in designing and evaluating performance creates both reliability and resilience. Reliability is achieved by exposing system weaknesses and vulnerabilities that can be corrected to enhance reliability in future and adjacent operations. Resilience emerges when we expose and correct deep organizational philosophy and behaviors.

Resilience is born in the organizational culture where individuals feel supported and regarded. Teams operate with deep ownership of organizational values, recognize and respect the tension between productivity and protection, and seek to make right choices. Communication occurs with trust and transparency. Leadership respects and gives careful attention to insight and observation from all levels of the organization. In this culture, people will self-assess, teams will synergize and cooperate to develop new and creative solutions when unanticipated circumstances arise. Individuals will hold each other accountable.

Safety within Operational Resilience is something an organization does, not something that is created or attained. A successful program will deliver a top-down institutionalization of culture that produces a bottom-up emergence of resilience.